Gregory Returns Home

Before the age of 2, Gregory was already deeply exposed to the harsh realities of racial violence and loss. Born in 1960 in Thibodaux, Louisiana, some of his earliest memories were witnessing pain, brutality, and death directed at and perpetrated against his Black community.

“I didn’t understand at the time the significant trauma it caused me at such a young age, but it shaped the way I saw the world.”

“Those images stuck with me for the rest of my life,” Gregory says. “I didn’t understand at the time the significant trauma it caused me at such a young age, but it shaped the way I saw the world.”

The turmoil and violence became too dangerous, and in 1962, Gregory’s parents relocated Gregory and his siblings to California in search of safety and a better future. While they faced financial hardships, Gregory found a sense of purpose and belonging. As a teenager, he thrived — serving as a young minister at his church, excelling in track, and beginning to build a future through football — until he broke his leg at 16.

Prescribed pain medication for recovery, Gregory quickly became dependent. The unaddressed trauma he had buried since childhood resurfaced, and he began relying on substances to cope. That dependence pulled him into a cycle of survival — one that led to addiction, escalating challenges, and petty theft, which ultimately led to his incarceration at age 17. He was sentenced to 68 years to life.

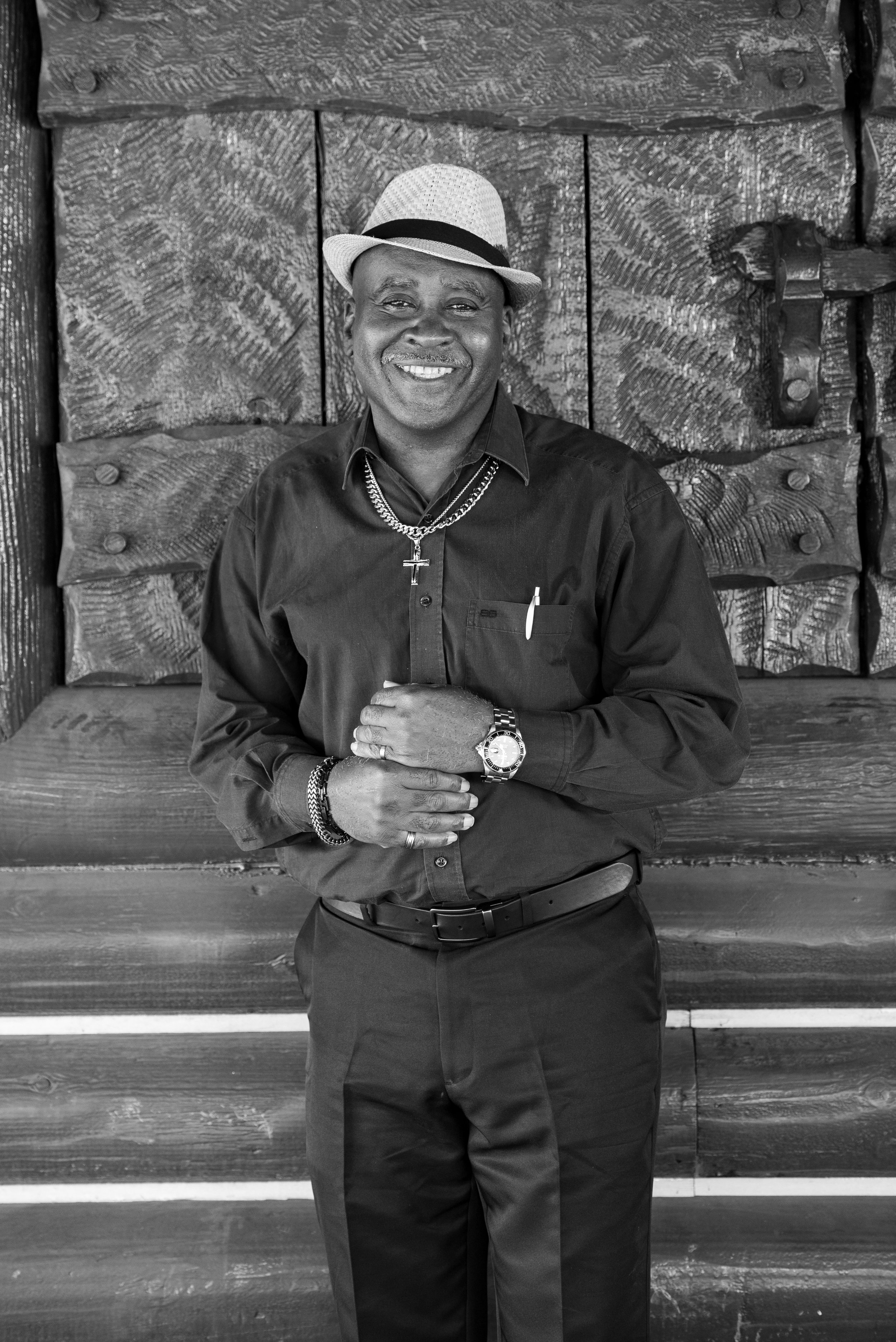

Gregory during his welcome home celebration. Thanks to our volunteer photographer, Ameer Mussard-Afcari, for capturing this moment.

While incarcerated, Gregory endured the loss of nearly everyone closest to him. Over the next five years, Gregory lost both parents, two brothers, his sister, more than 20 nieces, nephews, and cousins, and his wife and unborn child.

In 2008, after decades of grief, Gregory made a decision: he would break the cycle of pain and patterns of addiction, and direct his energy toward healing. That same year, he met a young man named Bo, the founder of GOGI (Getting Out by Going In), a peer-led self-help program rooted in purpose, healing, and personal responsibility.

GOGI is built around 12 practical steps that help participants confront the root causes of harm and redirect their lives. It addresses anger, domestic violence, addiction, emotional health, goal-setting, and job readiness. Through GOGI, Gregory began to unpack his trauma, reflect on his choices, and imagine a future beyond prison.

Bo became a close friend and mentor. After Bo was released on parole, his life was taken in a tragic motorcycle accident. “After Bo passed, I made a promise to keep his work alive,” Gregory says. “There was so much hurt around me. I wanted to help people move through it instead of being swallowed by it.”

“There was so much hurt around me. I wanted to help people move through it instead of being swallowed by it.”

In January of 2023, he was assigned a new cellmate — a young man in severe distress who told Gregory he was ready to give up on life. Gregory intervened immediately with compassion.

Gregory’s new cellmate, Christian, told him, “You don’t know me,” and Gregory replied, “I don’t have to know you to help you. I don’t see with my eyes. I see with my heart. And with my heart, I don’t see color. I see someone who needs love and help.” As a practicing Muslim, Gregory prayed for the young man every day, treating him as family and mentoring him with honesty and patience, drawing from everything he had learned through GOGI.

Gregory and his attorney Rebecca celebrating his homecoming at his welcome home celebration.

Around that same time, at age 64 and battling serious health issues including several tumors and deafness in his left ear, Gregory received a letter from UnCommon Law, offering him representation. He'd long been on UnCommon Law's waitlist, and his turn was up. He expressed interest in the offer, and he was introduced to his new attorney, Rebecca Berry.

“Becca was different than any other lawyer I’d ever seen or heard of,” Gregory says. “She showed up with her whole heart. Every single week. She even fasted for Ramadan with me. She became my family.”

Rebecca visited Gregory weekly and stood by him through the turmoil of his first and second court dates related to possible resentencing, which were happening at the same time as his parole process. Rebecca refused to give up on either process, even when the process felt impossible. “I got to know Gregory on a deeper level — his dreams, his grief, his accountability, his hope,” Rebecca says. “After the second resentencing court date, when he felt completely defeated, I sat with him in that pain. I knew who he was becoming, and I wasn’t going to let the system overlook that.”

“I sat with him in that pain. I knew who he was becoming, and I wasn’t going to let the system overlook that.”

It took a full team supporting the case — research, record gathering, resentencing expertise, and moral support through every setback. Rebecca says. “I was overwhelmed with gratitude for this village who held me and Gregory through all of the turmoil.”

When the time came for his third and final resentencing court date, Gregory didn’t know what to expect. During the hearing, a courtroom officer announced that someone had asked to testify. Gregory looked around but didn’t recognize anyone.

An older man stepped forward. As he reached the stand, he began to cry. The judge asked, “Sir, what’s wrong?” The man introduced himself as George and said he wasn’t there on behalf of any agency. He was there because Gregory had saved his son’s life.

After deep struggles, Christian, Gregory’s cellmate and George’s son, had turned to Gregory for hope. Gregory had supported him through that dark period and encouraged him to reconnect with his father. George told the court he had come simply to thank Gregory in person. But when given the opportunity to speak, he said to the judge, “If it wasn’t for Gregory, I wouldn’t have a son.”

“If it wasn’t for Gregory, I wouldn’t have a son.”

That testimony shifted the tone in the courtroom. For the first time, the judge began to see Gregory not just by his record, but by the tangible impact he had made on others’ lives. Then Gregory spoke from his heart, and the court granted a recall and resentencing under California law, reducing Gregory’s sentence and making him eligible for immediate release. “When the judge ruled in his favor, it reminded me that miracles happen when we align with them and courageously wield our power as advocates for love, healing, and justice,” Rebecca says.

Gregory was released late at night in July of 2025 wearing only a paper suit and without any belongings. Once again, George showed up, this time to drive Gregory to transitional housing arranged by UnCommon Law legal assistant Justin Anderson.

After more than 48 years in prison, Gregory returned home.

Now 65, Gregory is already dedicating his time to helping others. Every day, he brings food to people experiencing homelessness in his community. “I want to be an At-Risk Youth Counselor,” he says. “Our children are following in the footsteps of their parents — dying, going to prison, joining gangs. I’ve lived that cycle. I want to interrupt it.”

Gregory’s ultimate goal is to start a Youth and Women’s Council program for people impacted by domestic violence and incarceration. “I’ve lost so much in this life,” Gregory says. “But I still have love to give. Helping people is the only thing I want to do.”

Gregory with his sister Clara, his cellie Christian, Christian’s father George, Christian’s mother, and UnCommon Law staff Rebecca and Justin celebrating his release at his welcome home reception.

Photography by Ameer Mussard-Afcari.